Ms Rachel Noble PSM, Director-General of the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD)

Inaugural speech to the Australian National Security College (NSC).

1st September 2020

Long Histories – Short Memories:

The Transparently Secret ASD in 2020

In 2020, ASD is charged by the Government to fulfil three core missions.

To generate foreign signals intelligence that gives the Government insight into global strategic and military developments – and we do.

To protect our nation from cyber threats – from governments, to the private sector, small and large and to families and individuals – and we do.

To conduct cyber offensive operations – and we do.

I want to take you on our 73-year journey about how we became the agency we are today.

And I want to leave you with three key messages:

-

Firstly, ASD’s functions have been added to over the years but have not changed. Our cyber security mission, or information security as it was once known, is as old and as foundational as our sigint mission – the two are entwined and complementary.

-

Secondly, ASD’s functions have been a matter of public record since 1977. ASD’s lawful ability to collect intelligence about Australians has been public for nearly 20 years. Why? Because some Australians are not on our side.

-

Thirdly, ASD has intrusive and expensive capabilities which are aimed at our adversaries who seek to do harm to Australia and its interests. Keeping secret the nature of that capability and how we deliver our mission remains as vital today as it ever has been. What’s important is that we are transparent about what we are allowed to do under law.

What is it that we do and the history of our missions

As the Australian Signals Directorate nears its 75th anniversary in 2022 it’s timely to reflect on the history of the organisation and how its missions have been added to over that time in the context of Australia’s changing strategic environment.

Much of what I am about to tell you is already a matter of formal public record. But today I’m going to pull all the pieces together and tell you our story in the context of our historical timeline.

It is important that the functions of all intelligence agencies are made public and that those functions that we carry out are carefully governed and independently oversighted.

We do have intrusive powers and we certainly have very intrusive capabilities.

Being transparent about the uses to which these capabilities are put and what the law allows us to do is important. As is being clear and unequivocal publicly about which targets our powers can be used against.

There is good reason though why the question of how we gather this intelligence is kept secret. Keeping the how a secret is as important today as it ever has been.

In a context where our Prime Minister has recently likened our current strategic situation to that reminiscent of the 1930s and 1940s – it is perhaps a stark reminder that times do change and things do get better but they can also get worse.

World War II

ASD’s early role was to bring together civilians and Australian Navy, Army and Air Force personnel to support General MacArthur’s south-west Pacific campaign and the US Navy’s 7th Fleet Commander by intercepting and decoding enemy radio signals. After the war the government gave in-principle agreement to the creation of a new signals intelligence organisation, the Defence Signals Bureau, on 23 July 1946. Bureaucratic in-fighting unfortunately delayed formal approval by Cabinet until 12 November 1947.

Created by amalgamating the Central Bureau and the Fleet Radio Unit in Melbourne, the Defence Signals Bureau’s official birthday is 1 April 1947 and the new Bureau opened at Albert Park Barracks in Melbourne on the 12th of November 1947. Its role was to exploit communications and be responsible for communications security in the armed services and government departments.

Albert Park Barracks was a pretty awful place a collection of WWII huts which froze in winter and burned in summer. There was even a Heat Committee that roamed the corridors on the hottest days to ensure the temperature had reached 100 degrees Fahrenheit before staff were allowed to go home. Today it would probably be deemed unfit for human habitation.

We also had substantial assistance in the form of technology and personnel from our counterpart organisation in the UK, the Government Communications Headquarters, or GCHQ.

This laid the foundations of what became known as the Five Eyes Sigint partnership of the US, the UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

And I will go on record here as saying that this alliance of like-minded states is the most powerful, effective and enduring intelligence partnership the world has ever known.

The Bureau was renamed the Defence Signals Branch in October 1949 a title it retained until January 1964 when it became the Defence Signals Division.

When the newly-badged Defence Signals Directorate finally moved to new, purpose-built accommodation in Victoria Barracks in July 1979, James Killen, the Minister for Defence, sent ASD this encouraging message:

”We cannot talk about the activities of the Directorate. The national interest, and, indeed, the wider interest of civilised mankind, sweep you to silence. Can I say that in the years to come our people will look back with gratitude to you for your devotion.

It would be wrong to conclude that because a man cannot speak if he is not heard.

Silence has forever been a part of courage”.

I guess at this distance we can forgive the gender specificity and just thank the late Sir James for the generosity of his words.

ASD’s core missions – to collect intelligence about foreign adversaries, and to protect the security of our own information from adversaries, has remained unchanged through the 73 years. Although, today, we have more stakeholders and customers for our security advice than we once did.

When I first started at ASD in the early 90s we called the protection role information security, today we call it cyber security. Our information security mission then was focused on the protection of military and government communications from foreign adversaries. Today ASD is charged with providing information security, or as we know it today, cyber security advice and assistance, to the whole nation. Our customer set has grown over the years, but the mission has not fundamentally changed. Nor has the reality that what we learn from collecting intelligence about others profoundly informs how we protect ourselves.

These two missions have always gone hand in glove. They are two sides of the same coin. The binding of these two functions is perhaps more important today than it ever has been.

Because we try to gather intelligence from foreigners’ communications we have deep insight about how to protect ourselves from – well – people like us.

Not only have we learned from 73 years of experience of managing an integrated workforce, we have also evolved that shared tradecraft to manage a far greater set of complex threats, from state actors to low-life opportunistic criminals – now targeting not just governments and the military, but our private sector, small business, families and individuals.

Posing such threats was once the remit of only great and powerful state actors. Now it is the remit of anyone with a mobile phone.

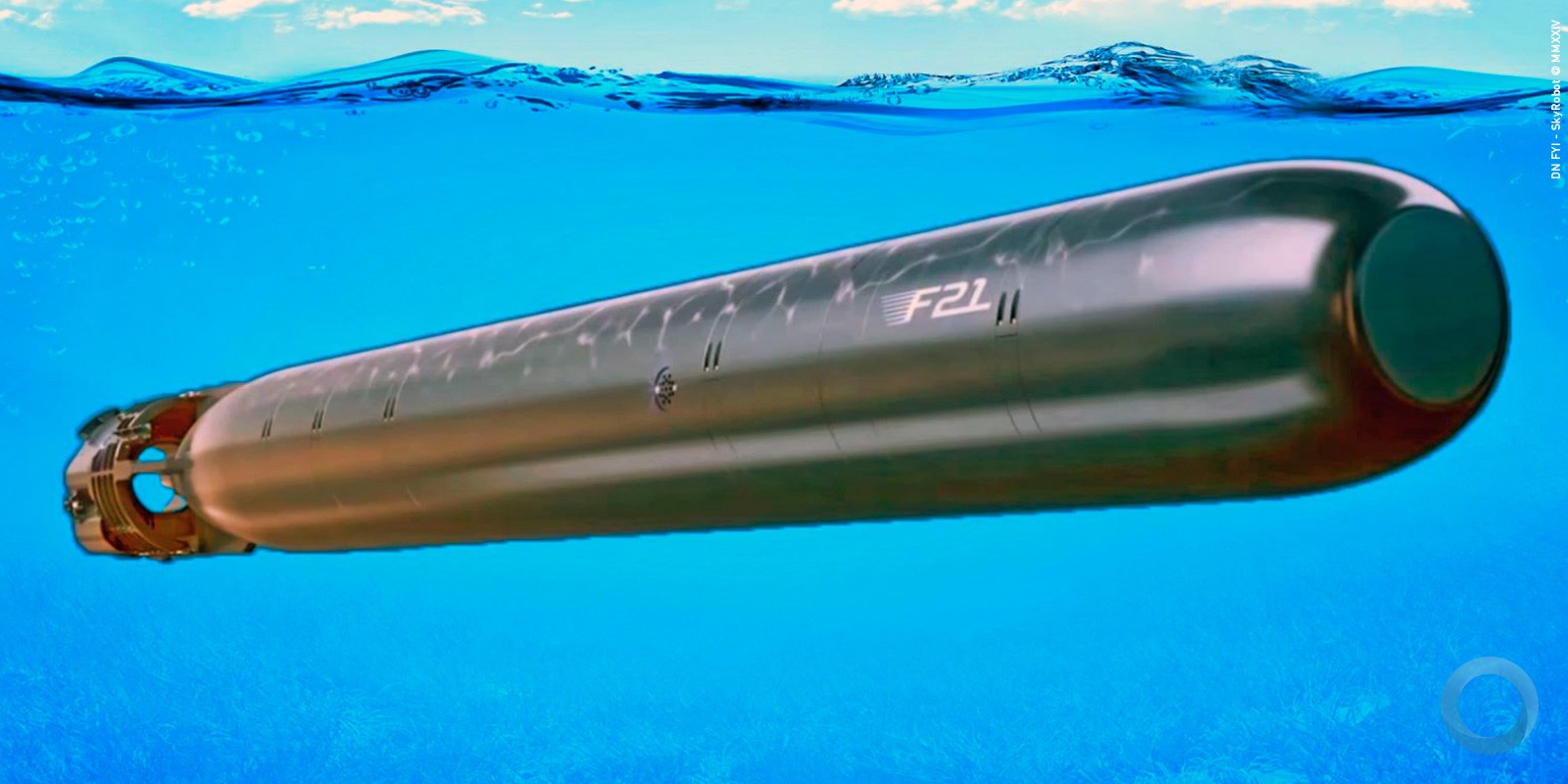

Information security played a pivotal part in what was arguably one of the most important military campaigns of World War II—the Battle of the North Atlantic.

This battle was waged from 1939 until the defeat of Germany in 1945.

The German Navy relied on the Enigma machine to encrypt its message traffic. They considered it unbreakable, and felt safe exchanging relatively large volumes of information between U-boats and shore command.

However, as a result of captured code material and the code breaking expertise of the British, the Enigma code was broken—for a short time in mid-1941 and again, with greater success, in late 1943.

During the periods of code breaking success, the number of Allied ships that were sunk began to decline, in part due to the knowledge of the location of German U-boat patrols.

While not the solitary reason for the North Atlantic victory, the Allied exploitation of German encrypted information changed the game for one of the longest and most complex naval battles in history. The Germans were confident that their information was safe, and they continued to use Enigma – to their detriment.

If a leak had made it clear to the Germans that the British were able to read their encrypted messages, we can only ponder now about how any German response might have impacted the Battle of the North Atlantic.

But the value gained from Enigma intercepts was undermined by a serious communications security failure which allowed the U-boats to detect and hunt down allied convoys in the North Atlantic. The German Navy’s own signals intelligence and cryptographic service, the B-Dienst, broke the British Naval Combined Cipher No. 3 in October 1941.

This cypher was used by the British Royal Navy, and later the US Navy. One estimate suggests 70 per cent of the convoys intercepted by U-boats between December 1942 and May 1943 had been primarily located with intelligence based on the German exploitation of Naval Cipher No. 3.

The discovery of this vulnerability in May 1943 and subsequent measures to improve communications security gradually deprived the B-Dienst of this source of intelligence.

Good communications security was just as important as intelligence obtained through Enigma to the safety of allied convoys.

ASD is both the poacher and the gamekeeper. Both sides of our brain work together to protect ourselves from people like us. We do sigint and cyber security. And we’ve been at it for 73 years.

1977 – Hope Royal Commission

In 1977 the HopeRoyal Commission marked the first occasion where the functions of the Defence Signals Division were made public.

On 25 October 1977 the Prime Minister made a speech in the House of Representatives about the outcomes of the Royal Commission on intelligence and security.

Prime Minister Fraser said of the Defence Signals Division that it was “…an organisation concerned with radio, radar and other electronic emissions from the standpoint both of the information and the intelligence that they can provide and of the security of our own government communications and electronic emissions. It is an agency which serves wide national requirements in response to national priorities”.

He went on to say, “…In close conjunction with the Defence Force, DSD provides a capability which is just as much an integral and essential part of a modern defence posture as a capability in air or ground defence or maritime surveillance. That capability is a sophisticated one for which long periods of training and development are required. The royal commission said that ‘the preservation of secrecy as to the agencies operations is vital”.

It was through this Royal Commission that the recommendation was made that the Defence Signals Division “…be re-styled as the Defence Signals Directorate” and made responsible to the Secretary of Defence.

“In discussions of intelligence matters…” the Prime Minister went on to say “…this Government will not provide further information about DSD nor confirm or deny speculation or assertion about it”.

1988

In June 1988 the Government decided that the Defence Signals Directorate should move to Defence Headquarters at Russell Offices in Canberra to ensure a close relationship with Defence and other intelligence agencies and its customers.

It was not long after that that I joined ASD as a code breaker. I didn’t like that job at all. I just thought I’d share that with you. I’ll tell you about that maybe in a different speech, and about what we hope we’ve learned from how we have historically failed to engage women in STEM. Here’s my spoiler alert – don’t starve them of human contact and make them sit alone with a computer all day.

But I digress.

The ISA 2001 and Australians

In 2000 work began between ASD and ASIS to develop the Intelligence Services Bill. ASIS had sought to make public its functions in legislation as a result of the Samuels and Codd Commission of Inquiry in 1995, but that work had been dormant for some time. ASD initiated the development of the Intelligence Services Bill as changing technology had inadvertently rendered some of its collection activities potentially illegal, and ASIS joined together with ASD at that time to place both agencies' functions in statute.

The Intelligence Services Actachieved Royal Assent on 1 October 2001 – only 21 days after the world witnessed the horror of the terrorist attacks on the United States.

In 2001 the then Foreign Minister, Mr Downer, in his second reading speech introducing the Intelligence Services Bill to the House of Representatives described ASD as “Australia’s national authority for signals intelligence and communications and computer security, and in that capacity provides an important service to the government and the Defence Force. “

The Intelligence Services Bill set out for the first time in legislation “…the control and accountability framework…” for ASD and in that speech on 27 June 2001 Mr Downer remarked the bill would create “…a balance between greater openness and the need for continued secrecy”.

At that time the activities of ASD were already subject to extensive oversight set out in the 1986 Inspector General of Intelligence and Security Act. In describing the functions of ASD, Mr Downer said both ASIS and ASD have “…an external focus in the furtherance of Australia’s national security, foreign relations and national economic well-being. Therefore, both agencies are empowered, under close government oversight and control, to collect intelligence information in accordance with national priorities and long-standing intelligence tasking mechanisms, and to distribute that intelligence”.

He also made clear that ASD“may provide assistance in various forms to Commonwealth and state authorities concerning the security and integrity of information, and in relation to cryptography and communications technologies”.

In fact the Act itself (section 7) makes clear that ASD is to perform its functions “to obtain intelligence about the capabilities, intentions or activities of people or organisations outside Australia…”

It was at this time that the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security was created to oversight the activities of ASD, ASIO and ASIS. ASD was initially not included at the time of the Intelligence Services Bill’s introduction on the rationale that it was within the Defence Portfolio and thus was already subject to oversight by the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee and the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, however the Joint Select Committee on the Intelligence Services recommended its inclusion – a recommendation accepted by the Government.

The debate on the Bill at the time was bi-partisan in nature, but in his second reading debate, Senator Faulkner, acknowledged that the Bill would “…empower ASD to obtain information in respect of foreign persons and organisations overseas and Australian persons and organisations overseas”.

He remarked “It is clearly possible to envisage circumstances in which intelligence collection related to an Australian person would be appropriate and desirable. An Australian person engaged in terrorist activities overseas is one obvious example” he said.

It was his intervention and a suggested amendment to the Bill which created the modern day arrangements for such activities, whereby a ministerial authorisation of any intelligence collection, or other activities relating to Australian persons must be obtained.

These written authorisations must be in place for such collection or other activities to occur and cannot exceed six months duration unless renewed by the Minister.

These activities must be connected to ASD’s legislated functions and they are activities that:

-

present a significant risk to a person’s safety

-

where a person is acting for, or on behalf of, a foreign power

-

activities that are, or are likely to be, a threat to security

-

activities related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction or the movement of goods which would be subject to Australia’s defence export controls

-

activities related to a contravention, or an alleged contravention, by a person of a UN sanction enforcement law [which was added in 2011]

-

committing a serious crime by moving money, goods or people

-

committing a serious crime by using or transferring intellectual property, or

-

committing a serious crime by transmitting data or signals by means of electromagnetic energy.

Faulkner said “…An Australian person engaged in terrorist activities overseas, whether directed against our nation or any other country, would clearly be a legitimate intelligence target”. He also said “People smuggling would be covered, as it relates to an aspect of national security, that is our border control”.

Such an approach he said would be “…broadly comparable to the special powers warrants provisions of the ASIO Act”. And thus it was agreed. And these are the rules by which ASD still operates today – nearly twenty years later.

In relation to the privacy of Australians the bill set out for the first time that the responsible minister for both ASIS and ASD must make written rules regulating the communication within government, and the retention of intelligence information concerning Australians and Australian corporations.

Previously, ASD had operated under guidance known as the Rules on Sigint and Australian Persons, which governed its activities in relation to Australians.

However, though approved by Cabinet and monitored by IGIS, the Rules did not provide statutory protection for Australians. ASD welcomed the additional safeguards mandated by Parliament.

The Act makes explicit that the Attorney-General must be consulted in the development of these rules. The IGIS also monitors compliance with the rules.

Shortly after the Act received Royal Assent, ASD embarked on a comprehensive training course for all staff to ensure that they understood and were fully compliant with the new obligations and responsibilities that were now required by statute.

This was a major cultural change. Under the old regime, an infraction of an Australian’s right to privacy could have been treated as an error of policy or administration, and dealt with accordingly. Now, it was contrary to law.

ASD worked extremely hard, in concert with IGIS, to embed a culture of compliance in the very DNA of the organisation.

For nearly 20 years ASD‘s role in relation to intelligence collection against Australians has been laid bare on the face of legislation.

It is hardly a modern revelation that ASD has this role.

Transparency is not a new feature of our story – some people may have just forgotten what has already been said over many years.

And I’m sorry if this is news to you but not all Australians are the good guys.

Some Australians are agents of a foreign power.

Some Australians are terrorists.

Some Australians take up weapons and point them at us and our military.

Some Australians are spies who are cultivated by foreign powers and are not on our side.

Our allies have similar powers. And as I have described, there are many careful controls which also protect Australians from ASD and its capabilities.

I want to underscore this point when it comes to intelligence collection and cyber offensive operations. ASD is a foreign intelligence agency. It is a matter for ASIO to concern itself with Australians who may pose a threat to our way of life.

ASD cannot, under law, conduct mass surveillance on Australians.

It is true, as is evident from ASD’s functions being added to over the years, that agencies must and do have carefully considered conversations about how to manage contemporary threats, including whether the management of such threats might ultimately involve legislative change. And after doing so agencies will provide advice to Government about their options. The Government then decides how best to address any risks in our security architecture – it is the role of elected officials, not public servants, to weigh threat and risk with the national interest. That’s how a democratic system of Government works.

As I said, ASD cannot, under law, conduct mass surveillance on Australians, nor has it ever sought to.

2010 – The rise of cyber

After my foray into code breaking, I slowly made my way to the branch within ASD known as Q branch which is now the Australian Cyber Security Centre.

ASD has long had branch names that mean nothing. This is based on the rationale that it makes it hard for the adversary to ever work out how you are organised and how many there are of you – which is an operational security approach that many intelligence agencies maintain today. This branch name, however, unlike the others in ASD, did have a meaning. The Q stood for quartermaster. The keeper of the keys. We still keep the keys today. It is one of the most important functions that ASD still performs – to generate the cryptographic material that encrypts our government and military communications to keep them safe.

Q branch or information security branch was also where ASD’s long-standing communication security role was fulfilled. The evolution of the Internet, email and the general convenience of electronic communications soon meant that ASD stood up a Cyber Security Operations Centre in January 2010.

It was in November 2014 that the Cyber Security Operations Centre evolved into the Australian Cyber Security Centre, which was the next evolution of Australia’s cyber security capability.

As the internet and all the goodness that it has brought to our lives became more pervasive, so too came the realisation that it had provided a new and terrible vector through which malicious actors and criminals could seek to harm Australians.

2018 – Cybercrime disruption

On 15 February 2018 the Hon Michael McCormack, the then Minister for Veteran’s Affairs and Defence Personnel, made a second reading speech in the House of Representatives introducing amendments to the Intelligence Services Act.

These amendments implemented the recommendations of the 2017 Independent Intelligence Review.

These amendments established the newly named Australian Signals Directorate as an independent statutory agency within the defence portfolio reporting directly to the Minister for Defence.

It brought some cyber security functions from the Attorney-General’s Department and the Digital Transformation Agency into the Australian Cyber Security Centre.

The functions of ASD were also amended to recognise the expansion of ASD’s cyber security responsibilities “…to include providing material, advice and other assistance to any person on matters relating to the security and integrity of information which is processed, stored or communicated by electronic or similar means; and cyber security, which…” Mr McCormack said “… will allow the ACSC to liaise with industry. “

This is a significant milestone in ASD’s history. It marks the recognition that ASD’s communications security role, through its ACSC, had been expanded, in the era of the internet, to provide communications security, or as we call it today, cyber security advice to the whole nation – no longer just to government and the military.

The bill also amended ASD’s functions to allow it to combat cybercrime offshore.

And it included provisions that the Director-General must consult regularly with the Leader of the Opposition about matters relating to ASD.

In that speech Mr McCormack also said that “… the bill included an additional function for ASD to protect the specialised technologies and capabilities acquired in the performance of other functions. “The ASD…” he said “…cannot perform its important functions without being able to protect its tools to ensure the ongoing utility and protect Australia’s national interest”.

And here we are today.

In recent times the legislation governing ASD’s functions has been updated more frequently.

This reflects the rapid change of technology and the inherent challenges of writing legislation that is technology agnostic and future-proof.

This has become increasingly difficult as technology, and the imaginative and wicked ways our adversaries exploit it, is harder to predict. ASD needs to ensure it provides good advice to Government when current laws might unintentionally impede its effectiveness, consistent with its already legislated functions – just like it did in 2000.

Being transparently secret – veiled transparency

As the years have worn on the revelation of ASD‘s functions in the public domain have been made by successive Australian governments.

This has in part been motivated by the realisation that maintaining the trust of the Australian people in ASD is achieved by the Government being transparent about what intelligence and security agencies are asked to do. But, I would argue, not how it is done. The how must necessarily be kept a secret.

There are good reasons why intelligence agencies need to keep how they collect their intelligence a secret.

It is one thing for an adversary to imagine what our capabilities might be. It is entirely another thing to have that confirmed.

If our adversaries know for certain how we are going about it, they will almost certainly take steps to prevent us from doing so. Just like we would do.

The Government has made nearly 75 years of investment in ASD and its cyber security, intelligence gathering and offensive capabilities.

Some of our capabilities are unique in the world.

They are expensive and precious.

They give us insight into the threats posed to our great country and that of our close allies.

And as we have heard recently from the Minister for Defence:

“Nations are increasingly employing coercive tactics that fall below the threshold of armed conflict. Cyber attacks, foreign interference and economic pressure seek to exploit the grey area between peace and war. In the grey zone, when the screws are tightened: influence becomes interference, economic cooperation becomes coercion, and investment becomes entrapment. Transnational threats also remain. Terrorism, violent extremism, organised crime and people smuggling. The COVID-19 pandemic is still very much an active and a very unpredictable threat…All of these pressures are contributing to uncertainty and tension, raising the risk of military confrontation…”

And those posing the threat go to great lengths to hide their activities from us.

As we have become more sophisticated – so have they.

Our edge is based on them being unsure about what we might actually be able to do.

We want them to think that we are their worst nightmare in the hope that they will be deterred from their actions in the first place.

It is this foundational principle which is as true today as it was at its inception in World War II.

Why give away more to our adversaries than we need to?

Once we talk about how we do it – we can lose that capability for ever.

Arguments that support the idea that we should give up protecting our secrets just because learned people have thoughtfully speculated publicly about how we might go about collecting our intelligence, is not an evidence base to argue that we should confirm the accuracy of their speculations.

And leaking is not formal avowal.

The notion of ‘neither confirm nor deny’ is as powerful today as when it was expressed by Malcolm Fraser in 1977 and reinforced by Mr McCormack in 2018.

So transparency is important but not at the expense of us losing the very capability that we use to keep Australia safe. There is a careful balance to be struck.

We are in a near impossible game. The threat to our way of life is more real today than at any time I have known in my career.

So I leave you today with the three key messages that I started with:

Our cyber security mission has not been recently bolted on to ASD – it has always been an intrinsically intertwined part of our core mission for 73 years.

Our ability to collect intelligence on Australians is not new because not all Australians are the good guys.

And some things need to stay a secret for good reason.

I hope you have enjoyed the photos – it is our people over the years that have made ASD the potent and proud organisation it is – and I thank them for their dedicated service. And I look forward to welcoming our next generation to ASD.

“Silence has forever been a part of courage”.

Thank you.

Ms Rachel Noble PSM, Director-General of the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD)