The Economist

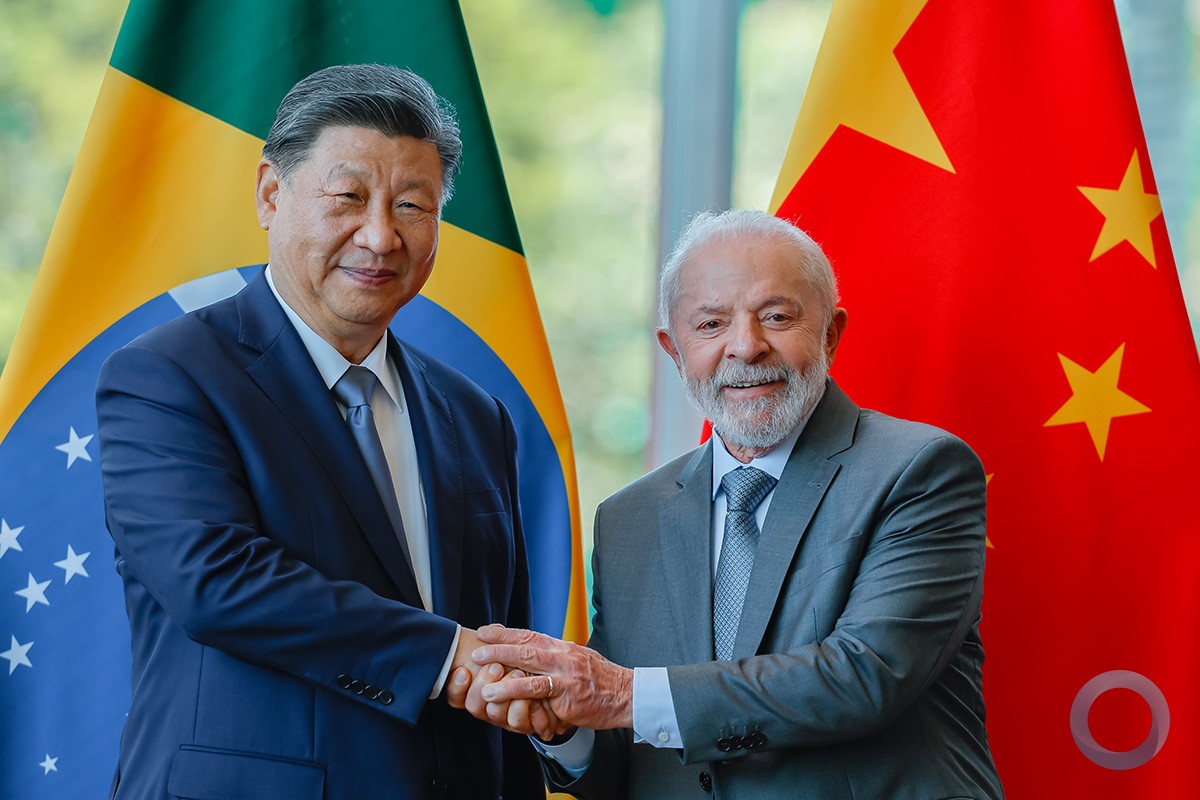

THE high point came last November, when Hu Jintao, China's president, arrived in Latin America to sign a series of trade and investment deals that heralded a new relationship between a rising superpower and a continent eager for economic growth. Nowhere was he greeted more warmly than in Brazil. Its left-leaning president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, sees China as the country's most promising business partner and an ally in boosting Brazil's global influence.

Toasting their “strategic partnership”, Lula predicted that trade with China would more than double to $20 billion in three years. China promised to invest $10 billion in Brazil, mostly in infrastructure. Brazil, along with Argentina and Chile, recognised China as a “market economy”, thereby constraining their ability to retaliate against imports. Brazil hoped for Chinese backing for its bid for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council

But the euphoria has already given way to a rising fear of Chinese imports, disappointment at the pace of investment and Brazilian anger that their government has weakened the country's trade defences without getting much in return. China is “not a strategic partner”, says Roberto Giannetti da Fonseca, head of trade issues at FIESP, which represents industry in the state of São Paulo: it merely “wants to buy raw materials with no value added and to export consumer goods.” As for infrastructure investment, Paulo Fleury, a specialist in the subject, detects “lots of smoke and little fire”. Meanwhile, on the diplomatic front, China is opposing Brazil's joint bid (along with Japan, German and India) for permanent membership of the Security Council, though this is to block Japan, its arch rival, rather than Brazil.

If the euphoria was overdone, so is the despair. China is likely to remain an engine of Brazil's economy, though more as a customer than as an investor. The threat from imports is certainly growing, but so are export opportunities. China, like the United States, is becoming an indispensable partner, to be handled with care.

The two countries are often described as “complementary economies”. Therein lies much of the terror and promise of their relationship. China's breakneck pace of development requires commodities that Brazil is well placed to supply. It also gives China an incentive to invest in Brazil's infrastructure, opening bottlenecks that hinder growth. Yet no big developing country is content merely to complement China, which seems unbeatable in the sort of manufacturing that generates lots of jobs. And the synergy that looks good on paper is proving hard to put into practice.

For an economy vulnerable to financial panics, trade with China has been a boon. According to government figures, Brazil's exports to China jumped from $676m in 1999 to $5.4 billion in 2004. Although imports surged too, Brazil ran a surplus of $1.7 billion with China last year. But, as FIESP points out, such trade mainly involves swapping commodities for more sophisticated products. Nearly 60% of Brazil's exports to China are primary goods, largely soya and iron ore. Imports from China are higher-tech and more varied, with electronics, machines and chemicals in the lead. Now China is making inroads into such labour-intensive sectors as textiles, shoes and toys, too.

Judging by official data, the Chinese threat looks small. In shoes, for example, total imports account for about 1% of Brazilian production. In other cases, China appears often simply to be replacing traditional suppliers. But such statistics omit goods that are smuggled into Brazil or are “under-invoiced” to dodge taxes. Some two-thirds of Brazil's pirated products are produced in China. More than a newly paved motorway, the symbol of Sino-Brazilian relations is a cache of 66,000 Brazilian army uniforms, which tax authorities recently discovered being smuggled into the country. Though labelled “Made in Brazil”, they were actually made in China.

Even where Brazil is competitive, it faces obstacles. Brazilian farmers still seethe over last year's rejection by China of soya shipments costing hundreds of millions of dollars. China claims they were contaminated; Brazilians spy a ruse to back out of costly contracts. Embraer, a Brazilian aircraft manufacturer, recently set up a joint venture to build short-haul jets in China, but sales have not measured up to expectations.

Blame for the slow pace of Chinese investment in Brazil lies with both countries. Brazil has yet to publish rules that would activate public-private investments in infrastructure. China imagined that it could build Brazilian railroads with Chinese labour in exchange for long-term contracts to buy commodities at fixed prices—two delusions in one.

From all this, a new realism is likely to emerge, including tougher diplomacy on both sides. In conceding market-economy status to China, Brazil “could have driven a harder bargain” than it did—for example, by securing an expansion of meat exports, says Renato Amorim of the Brazil-China Business Council. Under pressure from textile manufacturers and others, Brazil's government has now drafted rules for “safeguards” directed specifically at China, which has threatened to retaliate.

But realism does not ignore opportunities. With China set to expand its textile exports, Brazil could increase its 1% share of the cotton market dramatically, says Marcos Jank of ICONE, a think-tank. China's urbanising population will soon be demanding more Brazilian pork and poultry, too. According to the Inter-American Development Bank, China's trade barriers are generally in line with those of other developing countries and are gradually being lowered.

The result is likely to be a reshaping of Brazilian industry, not its destruction, says José Roberto Mendonça de Barros of MB Associados, a consultancy. He reckons that Brazil will retain its edge in a wide range of industries, including small cars, T-shirts, bathing suits and machinery for energy and mining. The country's remoteness and high transport costs will protect other industries, he adds.

Brazil will get its $10 billion of investment eventually, if investors are confident of turning a profit. Chinese companies do not want to become “the World Bank” of Brazil, says Charles Tang, president of the Brazil-China Chamber of Industry and Commerce. Both countries are better off without such illusions